Lately as a team we’ve been thinking a lot about flexibility and collaboration, and how one supports the other. As it becomes clear that the pandemic has had a permanent impact on working practices globally (Office for National Statistics 2021), current students can expect a mix of on-site and remote, and synchronous and asynchronous work in their future careers. Working flexibly in collaboration with others is therefore a skill that needs to be factored into curriculum design, and so we’ve been collecting examples of flexible and collaborative activities.

This post will demonstrate some of these flexible collaborative learning activities after giving a brief overview of what we specifically mean by “flexible” and “collaborative.” We’ll also note ways to prepare students to make the most of the opportunities to work together.

What does it mean to work flexibly?

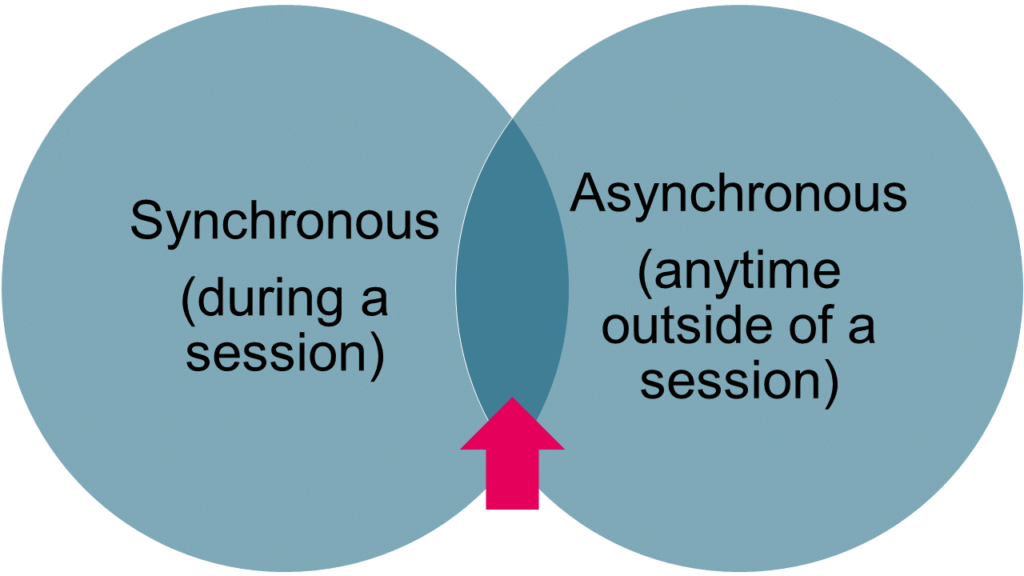

Flexible activities are the sort that fit right in the centre of the Venn diagram between those designed to happen during a session and those that happen outside of a session. It’s not only that these activities are flexible in terms of being able to complete them either synchronously or asynchronously, but that they can also span the two – so you might, for instance, start students off with a group activity during the session but expect them to continue working on it afterwards. Or you might set them a task before the session with the expectation that they will produce something together that they bring to the session, to refine their work with the help of the tutor.

But is it really ‘collaborative’?

Our team has recently been reflecting that when we talk about working ‘collaboratively’ we’re referring to a wide range of different ways to work together, and not always true collaboration. McLuckie and Topping (2004) produced work on peer-supported learning that identifies some of the nuances and explains the differences between work that is truly collaborative, versus that which more comfortably fits under definitions for co-operation or coaching:

- Collaborative – Students work together on a shared project.

- Co-operative – Students work on separate tasks that will be combined to create a shared final product.

- Coaching – Students take on a coaching role to assist in extending another student’s understanding.

Of course, lots of activities fit within a combination of two or three of these categories, and sometimes students might decide among themselves which approach they will take at which point in the process – perhaps they will meet to kick-off a project, then divide some of the work up to complete in their own time before coming back together and collaborating on revising and finalising their work (collaboration, co-operation, and then collaboration again). Or, perhaps, they may work entirely in a collaborative online space such as Microsoft Teams, sharing ideas and drafts asynchronously. Or they could evaluate each other’s work and give feedback before each writing up a reflective piece about their experiences of peer assessment as part of a joint summative portfolio (coaching and co-operation). With these sorts of activities, students have the potential to learn about working with others alongside the taught subject content, something we can help them to prepare for by discussing potential peer-learning approaches to the task and explicitly centring this learning as an outcome.

Preparing the students for peer-supported learning

Students might not be able to tackle these kinds of activities effectively, however, without preparation and careful scaffolding. For instance, providing examples and modelling how professional colleagues communicate in an online collaborative space (such as Microsoft Teams) helps students to be able to apply professional “netiquette” to their interactions and understand how the space can facilitate the exchange of ideas and feedback. In the same activity, students may also need some scaffolding that prepares them to navigate and use the digital platform being used. Even where the platform closely resembles social media platforms, we cannot assume that students will be confident with every new tool, regardless of whether or not they’ve grown up using digital technologies from a young age (Corrin, Lockyer and Bennett 2010).

Helping students to perform coaching or peer assessment tasks will also ideally involve some preparation built into the activity. Teaching colleagues know that giving (and receiving) meaningful feedback is not inherently easy, and so it’s vital to enable students to develop some of those skills before being asked to evaluate each other.

Activity examples

On our blog we’ve featured recent examples of practice from our School that have involved peer-learning activities:

- Taking the newsroom online: creating connected, authentic learning remotely: Broadcasting and Journalism creative used Microsoft Teams to create online newsroom environments to facilitate student collaboration and co-operation that mirrored industry practice.

- Student-generated and Student-led: Independent collaboration in Teams: Students built independent collaborative online communities within a language teaching module to continue the discussions they began during sessions.

- Together We Can Do So Much: Building a collaborative glossary: Students studying Academic English collaboratively created a glossary during a session that they could then add to and refer to throughout their studies.

We’ve also shared the slides from the workshop we gave on this topic on the National Teaching Repository:

The last few slides capture some of the suggestions our participants made for peer-learning activities they could try out, or have already tried out, with their students. We’re going to continue to collect more ideas for these sorts of activities, and would be pleased to hear from anyone who wishes to share one with us, or discuss ideas around something new they’re trying out in this area.

References

Corrin, L., Lockyer, L. and Bennett, S., 2010. Technological diversity: an investigation of students’ technology use in everyday life and academic study. Learning, Media and Technology, 35 (4), 387-401.

McLuckie, J., and Topping, K.J., 2004. Transferable skills for online peer learning. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 29 (5), 563-584.

Office for National Statistics, 2021. Business and individual attitudes towards the future of homeworking, UK: April to May 2021.